News

Those Who Strike the Sound: A Long Journey of Tetabuhan in Java

Long before Javanese society knew musical notation or orchestral theory, they had already mastered something far simpler: creating sound by striking objects. This practice gave birth to tetabuhan—a form of sound-making that functioned not only as music, but also as ritual language and social expression.

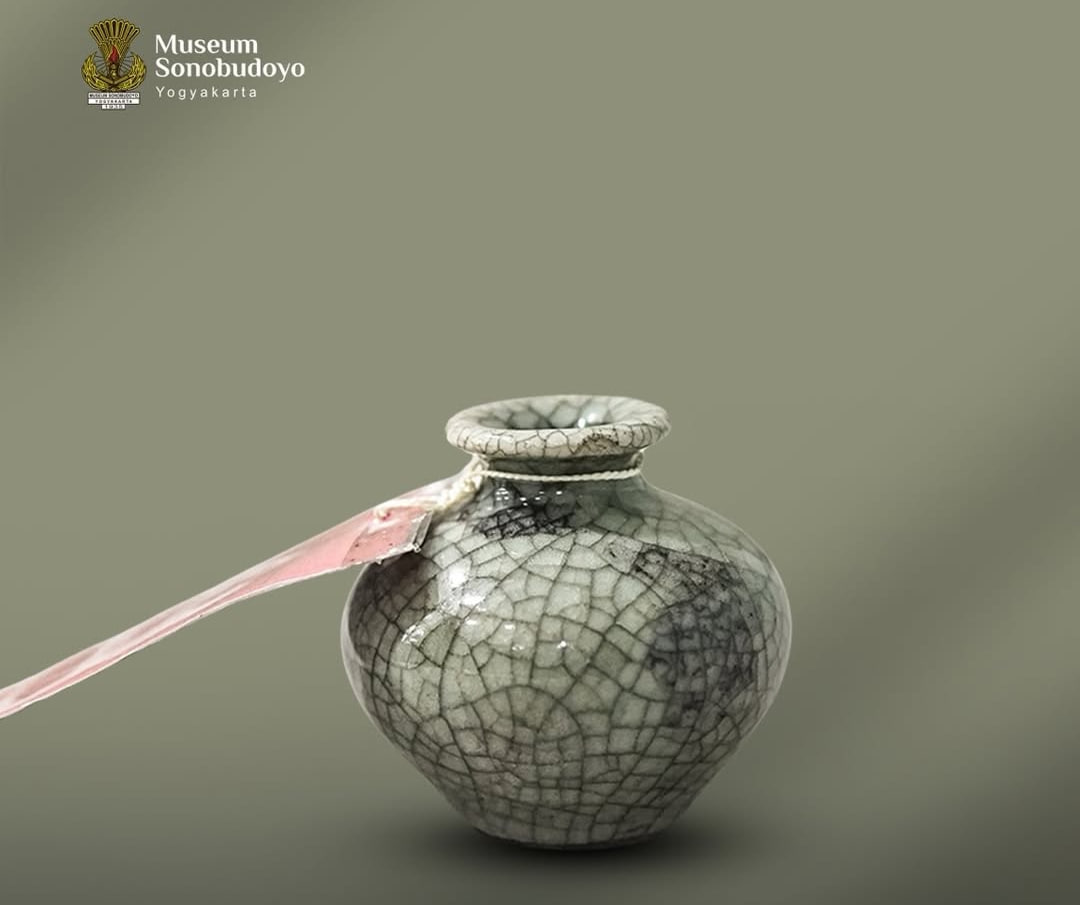

The roots of tetabuhan in Java stretch back to prehistoric times. Bronze objects such as nekara and moko, now displayed silently in museums, were once very much alive—played, struck, and resonating with meaning.

Nekara, Moko, and Conversations with Ancestors

In prehistoric belief systems, nekara and moko were used to summon ancestral spirits. The sounds they produced were thought to invite prosperity, especially rain. Yet their role was not purely spiritual. Moko also functioned as symbols of status, dowries, and valuable goods. Here, tetabuhan began to carry a dual identity: sacred and social, ritual and musical.

From Ritual to Performance

During the Hindu-Buddhist period, tetabuhan expanded beyond ritual spaces. It accompanied dances and royal ceremonies. The Randusari II Inscription from 905 CE mentions penabuh—musicians present during the inauguration of tax-free lands under King Balitung.

Instruments such as regang (cymbals) and gendang (drums) appear in Old Javanese inscriptions and temple reliefs. One can still see them carved into the stone panels of Borobudur, frozen in motion yet rich in soundless memory.

Gamelan and Sacred Noise

By the Islamic period, tetabuhan evolved into a more structured musical system: gamelan. Struck and plucked instruments were organized into an ensemble played exclusively during important royal events.

One of these was Sekaten, part of the Grebeg Mulud celebration commemorating the Prophet Muhammad’s birthday. For seven days and nights, palace gamelan was played in front of the royal mosque. The climax, Grebeg, involved each palace military unit producing its own sound, creating a loud and vibrant atmosphere. The word grebeg itself is believed to come from gumarebeg, meaning crowded and noisy.

When Western Sounds Arrived

By the 18th and 19th centuries, Javanese musical life became even more complex. European instruments entered the scene. Some, like the piano, were combined with gamelan and played in royal courts. In the 1920s, such experimentation was led by German artist Walter Spies in Yogyakarta.

Meanwhile, European orchestras entertained colonial communities in their own social halls. Two sound worlds coexisted—sometimes intersecting, sometimes separate.

Today, this long sonic journey can be traced at Museum Sonobudoyo, where instruments that once shaped rituals, ceremonies, and celebrations now quietly preserve the memory of Java’s rich tradition of tetabuhan.